Return to Hell

“It’s

the first time I’ve come to this hell hole. I live in Brescia, where

I was working along with my father, but since the crisis we haven’t

been able to survive. We lost our street vendors’ permit and my

father got ill. We live in a slum, and I’ve been

going

round Italy working on the land. Some of my friends told me to come

to Campobello for the olive harvest and earn some money, but instead

I’ve found myself sleeping in this place, finding it difficult to eat

because I’ve got no money, and what’s more I have to work the whole

day to earn just €20, because they work you to the bone down here.”

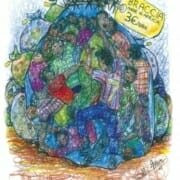

These are the words of ‘A’, 27 years old, who is one of the 1,400

people who have populated – and are still present in – the fields

of Campobello di Mazara. We went back ten days ago to see how the

situation at the “Ciao Ousmane” camp has fared. In comparison

with last year, the mood was much worse. One year has been enough to

improve the conditions of the place, that is, to provide dignified

conditions to those who work for us, who take care of our trees and

who, with so much dignity, attempt to put together some money to

live.

“I’ve

arrived in hell – actually, I’ve returned to it, because I’m

reliving the same situations which I experienced in the camps in

Africa which I passed through before I came to Italy. I had promised

myself that I would rather die than live in the filth, the

degradation, just smell the stench…”

‘I.’, 22 years old, from Sudan, confirms for us that the camp is much

more dirty than last year, and more or less in a situation of

abandonment. It is unthinkable that two people alone (the workers of

the cooperative that have the task of assisting the migrants with

their needs) can run a camp of 1,400 people. This year there have

been more people in the context of a poorer harvest, which has

created specific problems.

One main difficulty that we have been able to witness derives from

the institutional agents who, despite having received the funds, have

not managed to attain any improvement in the services provided by the

camp. Indeed, the camp was opened late, in relation to the beginning

of the olive harvest, because – according to the account of some

activists – over the intervening period it had been used as a waste

dump. And where did the money go? A question which finds no easy

response, given that the very same institutions, on our request to

meet with them, dug themselves in behind a “no comment.”

That money should have been used to repair the water boiler, to set

up more showers and toilets (there are only 12), to make some gutters

to unblock the surplus water. None of this was done. Some of the

migrants, instead of working at the harvest, stay in the camp to heat

water and then sell it on at 50 cents a bucket.

“We

are convinced that these people are lower than us, and can take

anything, this is the only way we can make them live like this”,

denounces one of the activists at the camp. He complains not only

about the total abandonment by institutional agents, but also by

associations which, having signed a protocol of understanding,

disappeared into thin air.

While walking among the tents, we could feel the failure not only of

the local institutions, but also our society. Our eyes cross with

people who are tired of bearing the signs of exhaustion, or with

those who, despite the great difficulties they face, show a desire to

keep on fighting, who want to go further because who cannot stop and

wait for a life with opportunities.

“It’s

like an African slum” declares another activist who accompanied our

visit to the camp. This year the work has been less, and many people

have remained in the camp, including those who play draughts made

from cardboard and bottle tops.

“I

came from Florence. I paid a ticket to work, but I can’t take only €2

for a box, I want at least €4.50, my dignity isn’t for sale…”.

“I haven’t worked, there’s so little work and now I’m stuck here

because I don’t even have the money to turn back”, R and S tell us,

both Moroccan.

Those who came back after last year wanted better wages than the

past, while those who are new, or without leave to remain, will do

anything just to have €10 in their pocket, to the happiness of the

owners of the olive groves. This is a war among the poor, a “blessed”

war which the landlords want, a race to the bottom, played out for

those who want to pay the least. It is a vicious circle of

exploitation. On one side there is the state which creates invisible

people, rejecting them, or revoking their right to the reception

system, or handing out a flurry of negatives at the Commission –

and on the other side there are the citizens who, harassed by large

multinationals which impose famine prices, have to hand the prices

down to the last rung – really the very last, because it remains

invisible.

All of this has serious consequences on people, creating fear, unease

and inhumanity. These are stories of the “unlife” on our streets,

which we pretend not to see. And we are building walls to make sure

we don’t have to enter into any kind of contact.

Yet again we ask ourselves: where are the institutions, whether civil

or religious? Those which could create points of meeting and

dialogue, which could create some kind of preventative work of

interaction, who are all so obvious due to their absence. Perhaps

their only objective is to allow for a labour force without rights

and at low cost.

And they’ve managed it this year yet again. The olives have been

harvested and the people have begun to leave the camp. Some go back

to their families, others will be exploited again in some other work

camp for another harvest.

For those who remain, like those friends who we met in the abandoned

farm houses, survival will not be enough. Among this group of 40-50

people there are some minors who have run away from some reception

hostel on the island. Their experience of abandonment is given some

support by their older brothers, the only form of guidance remaining

to stop them from sinking into the inferno.

N.B.:

at the time of writing, 30 November 2016, there are around 80 workers

still remaining at the camp, even though it has officially closed. On

December 1st

it will be reassigned to the local council. This is what remains of

the 1,400 slaves:

Alberto Biondo

Borderline Sicilia

Project

“OpenEurope” – Oxfam Italia, Diaconia Valdese, Borderline

Sicilia Onlus

Translation

by Richard Braude