The Christmas holidays and the solitude of the invisible

Article first published on December 30, 2020

The cries of outrage that accompanied the organization of the Christmas holidays in time of the pandemic, in addition to the general indignation surrounding the number of death due to Covid-19, takes on an even more paltry turn for those who cannot even afford to imagine celebrating Christmas.

Adama will have spent it in an abandoned train carriage, Peter in a cottage in the Marsala countryside together with 18 others invisible like him. As for her, Osas, will have been in the clutches of a man who will exploit her maybe after going to church for Christmas’ holy mass; Amadou on the other hand, will surely have remained in the Campobello ghetto in his hut made of wood and sheets, and finally Malik will have sought refuge in one of the many tents that at the moment are snapped up among the invisible people living in Palermo’s streets during quarantine nights.

As a matter of fact, Malik, himself smiles at my question about Christmas: “I smile because I hear and see a lot of people worried about these holidays that have to be done in the family. I wish I had the chance to be with my family not just for Christmas. This is my eighth or ninth Christmas I spend on the street; perhaps, thanks to the virus, this year I will not have people who will bother me with firecrackers. I have lost count because I am always alone, or in the company of some drunkard. We are truly alone and we don’t have a home to warm up. While you guys are all about the numbers this year due to Covid-19; try to think like so many of us, as you call them invisible, birthday parties, Christmas and many other holidays; for us it is always the same miserable evening, alone under a blanket and a cardboard in the hope that it won’t rain: this is my Christmas”.

Adama and Peter are not so happy to tell their situation, they feel more and more abandoned, given that due to Covid-19 there are fewer and fewer volunteers, and they do not even have the opportunity to see or talk to other people. For them too it will be a Christmas of hardship and loneliness. Peter, despite the presence of others invisible in the cottage, feels alone and will not have celebrated because he and the others do not even have the money to buy something special for the party; if all goes well, some of the usual rice will be on the menu that he will cook himself.

Amadou does not want to celebrate because he remained in Campobello waiting for his “boss” to pay him in order to proceed towards the next stage in the exploitation circuit. Moreover, he is worried because some of his friends left earlier to be hired in Rosarno, as he stayed in order to collect his friends’ money. But this money does not come, only the promises of payments arrive that slip week after week, leaving him with no desire to celebrate.

For Osas there is no Christmas that holds: “I am Santa Claus for many men, white and even black my brothers, I am the one who gives a moment of joy. But you don’t know that every time you leave me wounds that I cannot heal. Not even with Covid-19 you stop, and many have come to me after mass to take the gift. No, there will be no Christmas for us sex slaves”.

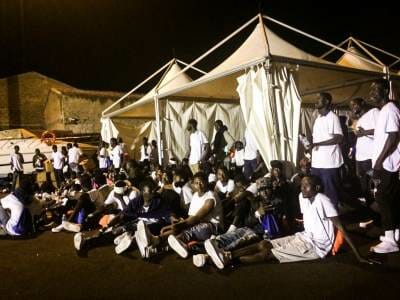

These are some stories of people who are experiencing the holidays like every day, oppressed by a system and a society that has crushed them and made them invisible slaves. Besides them, there are many other “last” of our cities who will experience the anguish of not knowing what will become of them, such as the many people locked up in quarantine hotels who are – still testing positive – alone in a room. In a state of continuous limbo some of them have not seen sunlight for 40 days. Also in the quarantine hotels there are migrants who – even if they tested negative for Covid-19 – remain prisoners because they can leave the structure only if they have a residence. But people who have just arrived in Italy remain days and days without any explanation, waiting for the prefecture to assign them to a CAS*.

There will be no party for the many who queue every day in front of the police headquarters without any social distancing, while helpless policemen observe people crowded together, waiting for their turn or to get an answer to the many requests that are not fulfilled due to problems due to Covid-19. Endless postponements and bureaucratic obstacles make life impossible for many migrants. Police stations that should be safe places and where legality should be guaranteed, are instead places where a woman with a baby has to stand in the rain in the middle of the street.

We have repeatedly denounced the way people wait in line at the Immigration Office of the Palermo police station, which perseveres with practices that, in addition to damaging people’s dignity, also put their health at risk. As a migrant wrote on social media, after yet another postponement by the police: “We are not animals of the government that puts us in danger. We have to stay outside to catch the virus, they stay inside. Their health is more important than ours. The police station is large, they don’t make room for us inside, we have to stay outside. Then, when they see two people on the street they say it’s not okay to walk together because of Covid. Instead, they leave a hundred of us outside the police station for us to catch the virus”.

There will be no party for all those people who have recently arrived in Lampedusa and transferred to Covid centers or quarantine ships. In Covid centers, unaccompanied minors, pregnant women and people with mental or physical problems are placed in promiscuity, for 14 days if all goes well. In the event of a positive swab, the period of isolation continues and the aftermath is a lottery, without any prize but only with the risk of ending up on the street with a rejection decree, because organizing transfers and finding places during the holidays becomes even more difficult.

2020 also leaves us a legacy of several irregular practices carried out by the institutions. Indeed, it is said that some entities managing reception centers, there were transfers – arranged by mistake – of people who had not carried out the swab or even who had tested positive, resulting in the consequent quarantine of the entire structure.

As for the transfers of unaccompanied minors to centers for adults, these are not errors but the implementation of authorized provisions of the Palermo Juvenile Court. An operator tells us that: “There are those who will turn 18 in a month, who will in two or three months, they have been transferred here, even though they could not stay in our facility, but we cannot refuse”. Apparently, it would not be the first time that this has happened in this period due to lack of places in the centers for unaccompanied foreign minors, who must be relocated after quarantine.

It is precisely this shortage of places that is leading to the authorization of the doubling of places in existing structures, some of which have gone from the original capacity of 15 to 30 for the emergency.

A system that, as per usual, finds in the emergency the justification for not guaranteeing the rights provided for by law. We are told that many minors, upon arrival, declare that they have family members in Italy but the reunions are not facilitated and it is preferred to park them for months, or even years, in the FAMI* centers in Sicily which are full.

A destroyed reception system on which, with the decree amending the security decrees, the opportunity to make a truly improving and structural change intervention was lost.

Covid-19 or not, lockdown or not, for many people the holidays are like every day, without the hope of receiving that gift they have long desired: the possibility of living a worthy life.

Alberto Biondo

Borderline Sicilia

*CAS: Centro di accoglienza straordinaria – Extraordinary reception center

*FAMI: Fondo asilo migrazione e integrazione – Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund

Translation from Italian by Anna Doumbia