Where The Tents Were: Stories of Rural Exploitation

During the three months of the olive harvest at Campobello di Mazara, people were constantly present to support the seasonal workers and alleviate their exhaustion and the difficulties. There were people who people gave their time and ideas, trying to provide a minimum of dignity to the seasonal workers. The institutions weren’t there, neither the prefecture, the trade unions, the labour office, nor the local council. They only woke up once the harvest was over in order to evict the labourers.

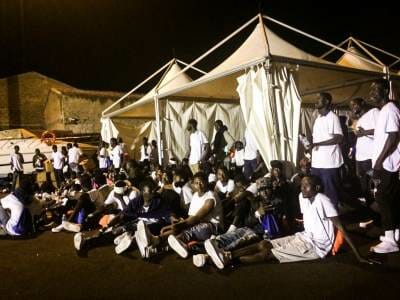

Once there was the Erbe Bianche camp with its tents, which we never accepted because no workers should live in such conditions. Instead they should receive that which is set down by law, i.e. bed and board – something which no employer was ever given to them. Once there were people who silently made a whole area rich with their blood, sweat and lives, such as Ousmane, the young Senegalese man who died from the explosion of a gas canister in the Erbe Bianche tent-city in 2013.

The institutions – the Trapani Prefecture, the mayors of Campobello and Castelvetrano, the trade unions complicit in the situation for decades, right up to the managers of the tax office – have chosen to simply hide the exploited. This is what was done by people who are meant to guarantee rights and legality. This is the reason behind not allowing anymore camp sites at Contrada Erbe Bianche, for the expressed motivations of hygiene and sanitary concerns, and because they were occupying a public space and even even a site of archaeological interest.

Today Erbe Bianche is an open air rubbish tip, an ad hoc dump created in order to block any tents. The locals did not complain this year, in fact they prefer a rubbish tip to people who might demonstrate the human price being paid to advance our economy. But this year too the olives needed to be harvested and the seasonal workers arrived from all over Italy, above all Senegalese workers with regular permits to stay, who hid themselves in the old cement plant, exactly where Ousmane died. After fruitless negotiations and meetings, proposals put forwards only to benefit farming businessmen with a not insignificant political support, around a thousand people were forced to live in even worse conditions than previous years, without water or electricity. But the institutions did have the courage to encourage employers to hire people and even house workers with tents on their own fields.

Along with other associations, we have – during meetings with the Prefecture – even asked for checks on employers and the housing conditions of employees, but no checks have been carried out. And so workers have told us about encampments inside agricultural companies without water or electricity or even portaloos. In some of statements, some employers have even said to have housed people in storerooms, like beasts. Fortunately some employers have also done their duty, i.e. officially hiring the seasonal workers and putting a roof over their head, but those who respect the law are still few and far between.

Listening to the unions, the labour office and the prefecture triumphantly present the figures simply invites more anger. Around 1,300 work contracts signed: they tell us that this is a huge success and two years’ ago there wasn’t even one contract. We do not want to underestimate the importance of the fact that finally there are contracts but at the same time – as we said at the round-table with the prefecture – most of these contracts are fictitious: the contracts are agreed for a few days but the employers make people work one or two months, or even longer. No one at the meetings took charge of verifying these claims, as they are all aware that this would mean closing in on a comfortable mechanism.

On a central level, the obligation for agricultural employers to communicate days worked by farmhands to the tax office on a monthly (rather than quarterly) basis has been postponed till January 2020 – yet another gift to our friends the businessmen who play with workers’ lives.

The aspect about which the institutions do not talk at all is the arrival of African gang-masters who systematically intervene in workers’ payments, negotiating the price for a box of olives (€3.50 on average) or per day (€40 for a whole day, €15 for a half day).

The lack of checks and controls and this merely superficial legality have de facto deprived workers of the possibility to access unemployment support, because the days resulting from the contract are not enough. They also cannot enter into housing contracts because they cannot provide enough guaranty.

Among the many workers affected by this, there is ‘E’, a 63-year-old Senegalese man, humped over from the pain in his legs, who told us that he has been in Italy for 33 years, and worked in a factory in Brescia for 25 of them. The factory closed down 2 years ago and he now tours the Italian countryside because no one offers a job to a 63-year-old man. “There isn’t work for the young guys, of course they don’t give me a job. But the young people aren’t any competition for this kind of hidden, hard work, so I have the chance to earn a little to feed my family. It’s taking a heavy toll on my health. I could deal with it all if there was just some attention for my rights, I haven’t been able to pay any tax for a long time because for 2 years now they give me fake contracts and I don’t know if I’ll live to see the pension I sweated away for all those years.”

The choice to exploit workers is one made with eyes wide open, a functioning part of an economic system that would collapse without them. When propose that the institutions carry out checks, they hypocritically respond by asking us to provide the names of the employers, as if they didn’t know them already, as if workers were free to report the exploitation to which they are subjected. “And if I tell you who exploits me, who’s going to give me any work?” ‘E’ told us as he walked away.

Where once there were tents at Erbe Bianche now there is only desolation and injustice. It seems that Ousmane’s sacrifice gained nothing.

Alberto Biondo

Borderline Sicilia

Project “OpenEurope” – Oxfam Italia, Diaconia Valdese, Borderline Sicilia Onlus

Translation by Richard Braude