Exploitation and neglect in the Trapani region

If you want a good idea of how the government

manages immigration, just take a trip to the province of Trapani. As we have often said and reported, Trapani is

the experimental laboratory in which the government tests out firsthand its

policies towards migrants (since the Serraino Vulpitta).

As well as the Milo CIE and the Salinagrande

CARA, migrants also dwell in gyms, tented cities, and in abandoned buildings in

the countryside, where hundreds are left vulnerable to exploitation. Migrants runaway from the Milo CIE on almost a

daily basis, and riots and protests are commonplace due to the complete lack of

assistance available since the Prefecture pulled the plug on the consortium

Oasis’ management contract.

At the Salinagrande CARA the situation balances

precariously between inmates, law enforcement, and operators who find

themselves in increasingly difficult working conditions, as the Prefecture

continues to fill a centre which should accommodate only 260 migrants (when in

fact it contains more than 400).

On top of this, the municipal transport

company of Trapani has decided to cease running the only bus route which passes

the centre, because “the migrants don’t pay for the ticket”. The

Prefecture won’t commit itself to providing the service.

In such a stressful and constrained

environment, migrants easily lose their temper for trivial reasons and quarrels

amongst inmates in the CARA have multiplied significantly in recent months.

This situation is the result of neglect and

the inability to make a thought-out migration plan, and so as in 2011, we have

an EMERGENCY!!

And, as we know, when we have an emergency the

government can act more freely, approving operation ‘Mare Nostrum’ and a new

reception plan.

What would you expect? Do you remember 2011?

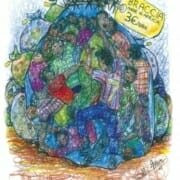

The plan envisages the filling (to exhaustion)

of all the existing centres, and the creation of a number of new centres, which

will all also be packed full. And the Prefecture of Trapani, as did the Civil

Protection in 2011, has put out a call for new reception centres, €30 for each

migrant.

A state of affairs, which as before, has seen

many throw themselves forward in the hope of making a bit of money. So many

hotels convert themselves into shelters, and abandoned buildings get rented by

various consortia in order to make centres for migrants.

Whoever lands on the shores of Sicily will be

sorted and put into a CARA, a CIE, a gym, or one of these new centres.

And those who do not arrive in Italy via

Lampedusa? Another problem, because those who arrive in Italy by

“land”, who present themselves directly to the police headquarters

asking for asylum (because they do not have the possibility to continue their

journey, for any number of reasons), are forced to live in abandoned buildings

close to the centres, or in tent cities in the Sicilian countryside, since the

centres themselves are overflowing.

After Alcamo and Marsala (if we focus on the

province of Trapani), tent cities flourish in Campobello di Mazara (as we have

seen for the last 5 years), where the olive harvest is about to finish, and

where more than 600 migrants have moved in hope of making some money, in the

hope of having a chance, in the hope of realising a dream. But how much does it

cost?

A great deal. As last month a Senegalese man

lost his life to burn injuries after the explosion of a camp stove.

With the end of the harvest, in these

following days many will leave and will move to Catania for the orange harvest,

which will create a new tent city, where exploitation will continue, where the

bosses will continue to humiliate the unfortunate, where landowners will take

advantage of the blindness of our politicians and the neglect of institutions.

But for many of us, it suits us not to see or

hear the screams of pain, so we can continue to pay less at the supermarket for

“our local” oil, or, our Sicilian oranges, the grapes of Marsala and

Alcamo, the potatoes of Cassibile, or the tomatoes of Pachino. Perhaps the

institutions do not intervene because maintaining this economy, now in complete

disarray, is dependent on this migrant labour force?

Posterity will judge, but for some of us it is

important to understand where these cheap products come from, so we can begin

to make some ethical choices, making our consumer choices critical and

supportive.

Borderline Sicilia Onlus/Alberto Biondo

Translation by Sally Jane Hole